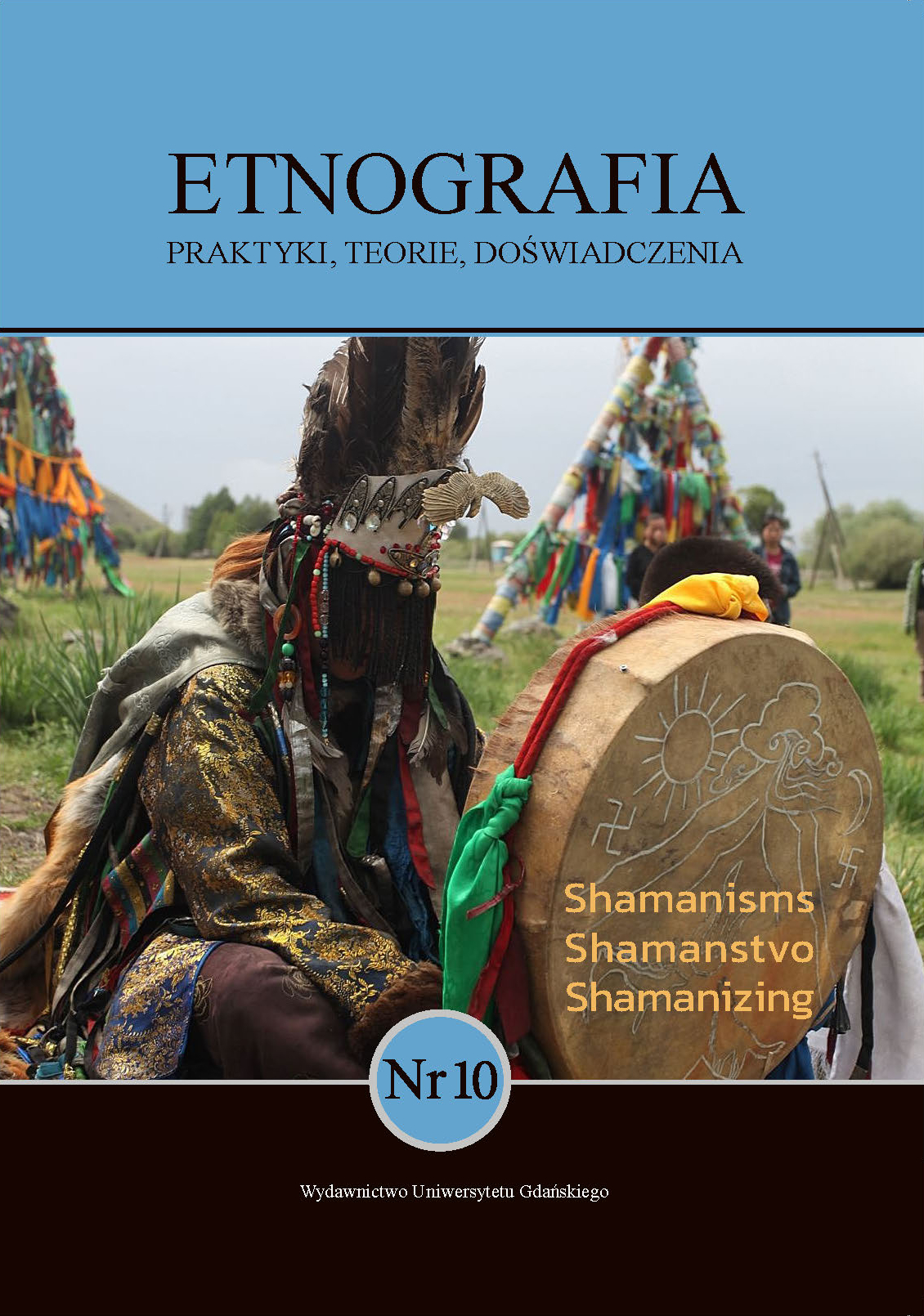

Shamans study shamanism: The world in the podcasts of Mongolian shamans

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.26881/etno.2024.10.03Słowa kluczowe:

Mongolian shamanism, böö, internal relation in logic, ontological turn, transcendental perspectivism, aminism, digital ethnographAbstrakt

The article analyses the social media activity of selected Mongolian shamans intended for dissemination of what they believe to be the correct knowledge about Mongolian shamanism. The Internet is a tool that, combined with their own creativity, allows them

to convey aspects of this phenomenon that are difficult to verbalize. On the one hand, the shamans present a great diversity, make use of different ideas (tradition, heritage, Buddhism), and are open to global movements such as neo-shamanism or environmentalism, but on the other hand, their statements exhibit some common, recurring elements about

the complex interdependence of human and non-human beings in a hierarchical cosmic system. This analysis is a voice in the discussion on the production of knowledge in various discourses, an attempt to incorporate the ontology of the “subject” into ethnographic theories, inspired by the work of philosophically oriented anthropologists.

Downloads

Bibliografia

Asad, T. (1993). Genealogies of religion: Discipline and reasons of power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bira, Sh. (2006/2007). Mongolyn tenger üzel ba tengerchlel. Bulletin. The IAMS News Information on Mongol Studies, 39(1), 5–66.

Bird‐David, N. (1999). “Animism” revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40(s1), s67–s91.

Bumochir, D. (2002). Mongol böögiin zan uil: Aman yaruu nairgiin töröl zuils. Ulaanbaatar: National University of Mongolia.

Bumochir, D. (2014). Institutionalization of Mongolian shamanism: From primitivism to civilization. Asian Ethnicity, 4, 473–491.

Burrell, J. (2009). The field site as a network: A strategy for locating ethnographic research. Field Methods, 21(2), 181–199.

Dalai, Ch. (1959). Mongol böö mörgöliin tovch tüükh. Studia Ethnographica, (1)5, Ulaanbaatar: Shinjlekh ukhaan deed bolovsrolyn khüreelengiin erdem shinjilgeenii khevlel.

Descola, Ph. (1992). Societies of nature and the nature of society. In: A. Kuper (ed.), Conceptualizing society (pp. 107–125). London: Routledge.

Kollmar-Paulenz, K. (2012). The invention of “shamanism” in 18th century Mongolian elite discourse. Oriental Yearbook, 65(1), 90–106.

Empson, M.R. (2011). Harnessing fortune: Personhood, memory and place in Mongolia. London: British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship Monographs.

Halemba, A. (2022). The Altai mountains have no ghosts: Ethnography beyond man. Polish Ethnography, 66(1/2), 11–27.

Holbraad, M., Willerslev, R. (2007). Transcendental perspectivism: Anonymous viewpoints from Inner Asia. Inner Asia, 9(2), 229–344.

Harvey, G. (2010). Animism rather than Shamanism: new approaches to what shamans do

(for other animists). In: Schmidt B., Huskinson, L. (eds.) Spirit Possession and Trance : New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Continuum Advances in Religious Studies (7), London: Continuum, 14–34.Humphrey, C., Onon, U. (1996). Shamans and elders: Experience, knowledge, and power among the Daur Mongols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Humphrey, C., Thomas, N. (1994). Introduction. In: T. Nicholas, C. Humphrey (eds.), Shamanism, history and the state (pp. 1–12). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hutton, R. (2001). Shamans: Siberian spirituality and Western imagination. London: Hambledon and Continuum.

IMS. (2024a). International Museum of Shamanism, youtube.com/watch?v=1SLcij-LiFU [access: 1.12.2024].

IMS. (2024b). International Museum of Shamanism, youtube.com/watch?v=OiLgEsyeDM8 [access: 1.12.2024].

IMS. (2024b). International Museum of Shamanism, youtube.com/watch?v=mncbz1Irrzc [access: 1.12.2024].

M-book. (n.d.). m-book.mn/surgamjit-tuuhuud-1 [access: 3.07.2025].

Manduhai, B. (2013). Tragic spirits: Shamanism, memory, and gender in contemporary Mongolia. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Marcus, G.E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 95–117.

Ochir, A., Enkh-Tüvshin, B. (eds.). (2004). Mongol ulsyn tüükh IV. Ulaanbaatar: Mongol ulsyn Shinjlekh Uchaany Akademi, tüükhiin Khüreelen.

Pedersen, A.M. (2011). Not quite shamans: Spirit worlds and political lives in the Northern Mongolia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Pedersen, M.A., Empson, R., Humphrey, C. (eds.). (2007). Editorial introduction: Inner Asian perspectivisms. Inner Asia, 9(2), 141–152.

Pürev, O. (1998). Mongol Böögiin Shashin. Ulaanbaatar: Admon Press.

Saincogtu, V. (2000). Amin shütleg I. Khökh khot: Övör mongolyn Ardyn khevleliin khoroo.

Sahlins, M. (1985). Islands of history. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shimamura, I. (2017). A pandemic of shamans: The overturning of social relationships, the fracturing of community, and the diverging of morality in contemporary Mongolian shamanism. Shaman, 25 (1/2), 93–136.

Sobkowiak, P. (2023). The religion of the shamans: History, politics, and the emergence of shamanism in Transbaikalia. Brill: Schöningh.

Spivak, G.Ch. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In: C. Nelson, L. Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Star TV Mongolia. (2024). youtube.com/watch?v=M4vmPI3Yeqw&t=106s [access: 1.12.2024].

Sükhbaatar, G. (1980). Mongolchuudyn ertnii övög: Khünnü naryn aj akhui niigmiin baiguulal, soyol ugsaa, garval MEÖ 4s ME 2– r zuun. Ulaanbaatar: Shinjlekh uhaany akademiin tüükhiin khüreelen.

Swancutt, K. (2012). Fortune and the cursed: The sliding scale of time in Mongolian divination. New York: Berghahn Books.

Swancutt, K., Mazard, M. (eds.). (2018). Animism beyond the soul: Ontology, reflexivity, and the making of anthropological knowledge. New York: Berghahn Books.

Szmyt, Z. (2020). Post-socialist animism: Personhood, necro-personas and public past in Inner Asia. Etnografia. Praktyki, Teorie, Doświadczenia, 6, 185–204.

Szmyt, Z. (2022). Zbyt głośna historyczność. Użytkowanie przeszłości w Azji Wewnętrznej. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

Szymura, J. (1990). Relacje w perspektywie absolutnego monizmu F.H. Bradleya. Kraków: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

Taussig, M. (1987). Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study of in Terror and Healing. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Tenger Shaman TV. (2023). youtube.com/@Tenger_shaman_tv [access: 1.12.2024].

Tenger Tailal Shaman. (2021a). Shaman Khosbayar Urantsetseg documentary, youtube.com/watch?v=fqubyYp8mlw&t=91 [access: 3.07.2025].

Tenger Tailal Shaman. (2021b). Tailal nevtrüüleg – Zairan Ts. Ganzorig oroltsloo

youtube.com/watch?v=VVBwTvTeIQw&t=2460s [access: 1.12.2024].

Uchan, A. ( 2021). Francisa Herberta Bradleya obrona metafizyki. Ruch Filozoficzny, 77(3), 119–140.

Underberg, N.M., Zorn, E. (2013). Digital ethnography: Anthropology, narrative, and new media. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Viveiros de Castro, E. (1998). Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(3), 469–488.

Zairan Khosbayar. (2024a). facebook.com/zairanhosbayar/videos/954272466226726 [access: 1.12.2024].

Zairan Khosbayar. (2024b). facebook.com/zairanhosbayar/videos/1520381038581234 [access: 1.12.2024].

Zairan Khosbayar. (2024c). facebook.com/zairanhosbayar/videos/724346543110979 [access: 1.12.2024].

Zapaśnik, S. (1973). Absolut jako projekt ideału moralnego w filozofii F.H. Bradleya. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa.

Zapaśnik, S. (2006). Walczący islam w Azji Centralnej. Problem społecznej genezy zjawiska. Wrocław: Fundacja Nauki Polskiej.

Znamenski, A.A. (2007). The beauty of the primitive: Shamanism and the Western imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Opublikowane

Jak cytować

Numer

Dział

Licencja

Czasopismo wydawane jest na licencji Creative Commons Uznanie autorstwa-Na tych samych warunkach 4.0 Międzynarodowe.

Uniwersyteckie Czasopisma Naukowe

Uniwersyteckie Czasopisma Naukowe