Między śmiercią i narodzinami. Biografia

Abstrakt

Nothing is more our own than our biography. Even the body, in which we spend our whole life, from birth to death, even this body, closest to us, our very own, the body that roots us into existence, although at the same time it betrays us every day, is only a loan with a definite if usually hidden payment deadline. It is only someone who, looking at the life of another person, says: gráphō, that shifts events, a sometimes extensive series of the body’s adventures, into the sphere of shareable words. Becoming a biographer with this declaration, he or she seeks meaning where there (probably) is none, and has never been. And yet, for reasons difficult to understand, for a long time the humanities looked down on life writing. Decreed by Barthes in 1968, for two or even three decades “the death of the author” continued to be an almost universal proclamation. Writing biographies seemed a menial task compared to developing sophisticated text exegeses or theoretical and methodological speculations, which, once announced to the world, were hardly taken up. But let us leave aside the humanists with their eternal troubles and dilemmas. Let us save biography as a form of grasping and understanding life – including one’s own life, as “everybody’s autobiography”, according to Gertrude Stein. But if it wants more than just popularity with readers, life writing should not stick to its old ways. Today, biographers face the obligation to develop new forms of biographical discourse. Full rights must be granted to fragmentary biographies, focused on one topic, in fundamental opposition to holistic approaches that span birth and death. To biographies selecting one role played by the protagonist over the years, or a single event, around which all other events are centred. To acoustic biographies or – this could be done – biographies in which the privileged way of settling into existence would be the eye and the act of looking, as was the case in Cézanne’s life. To parallel biographies, tangled together or perhaps multiply tied, which embrace the evident truth that every “I” establishes itself in relation to some “you” and some “him” or “her”. What seems most important in this new biography writing, however, is to cross the boundaries of individual life as soon as possible. Tense anticipation: are we going to see an electric arc in the gap between two lives, between being (of one) and being (of another), an arc that will connect them, establishing a continuity of existence. Between the one who died and the newly born.

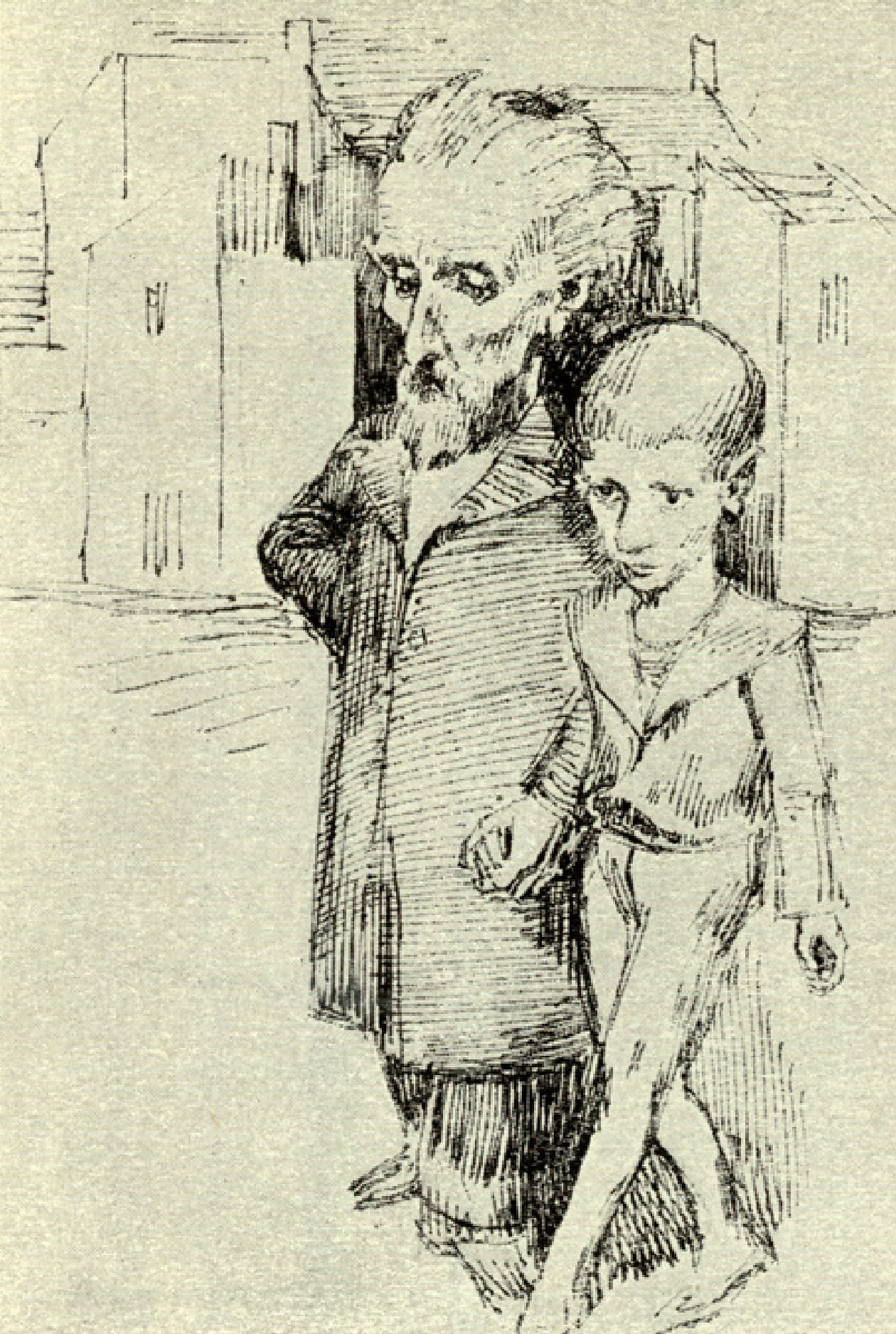

And hence Schulz, hence his biography.

Uniwersyteckie Czasopisma Naukowe

Uniwersyteckie Czasopisma Naukowe